The Hidden Lifeline of War

When most people picture D-Day, they imagine soldiers storming the beaches of Normandy, tanks rolling inland, and aircraft flying overhead.

But few realize that victory didn’t just depend on courage — it depended on fuel.

The Allied invasion of Europe wasn’t just an army on the move — it was a machine that needed constant feeding.

Every tank, truck, and plane ran on fuel. Without it, even the most powerful military would grind to a halt.

The problem was simple: how could the Allies supply millions of gallons of fuel to France without relying on vulnerable tankers?

The answer was a bold idea that sounded almost impossible:

“Let’s build a fuel pipeline… under the ocean.”

They called it PLUTO — short for Pipeline Under the Ocean — and it became one of the greatest engineering secrets of World War II.

Operation PLUTO: Churchill’s Daring Idea

The concept came directly from Winston Churchill’s obsession with logistics.

He understood that the success of the Normandy invasion wouldn’t just depend on firepower, but on supply.

In 1942, British scientists and engineers were tasked with developing a submarine pipeline system capable of pumping fuel across the English Channel — directly from Britain to the advancing armies in France.

It was an idea ahead of its time — blending engineering, innovation, and secrecy.

To the world, PLUTO was a myth. To the Allies, it was their hidden artery of war.

Building the Impossible: The Engineering Challenge

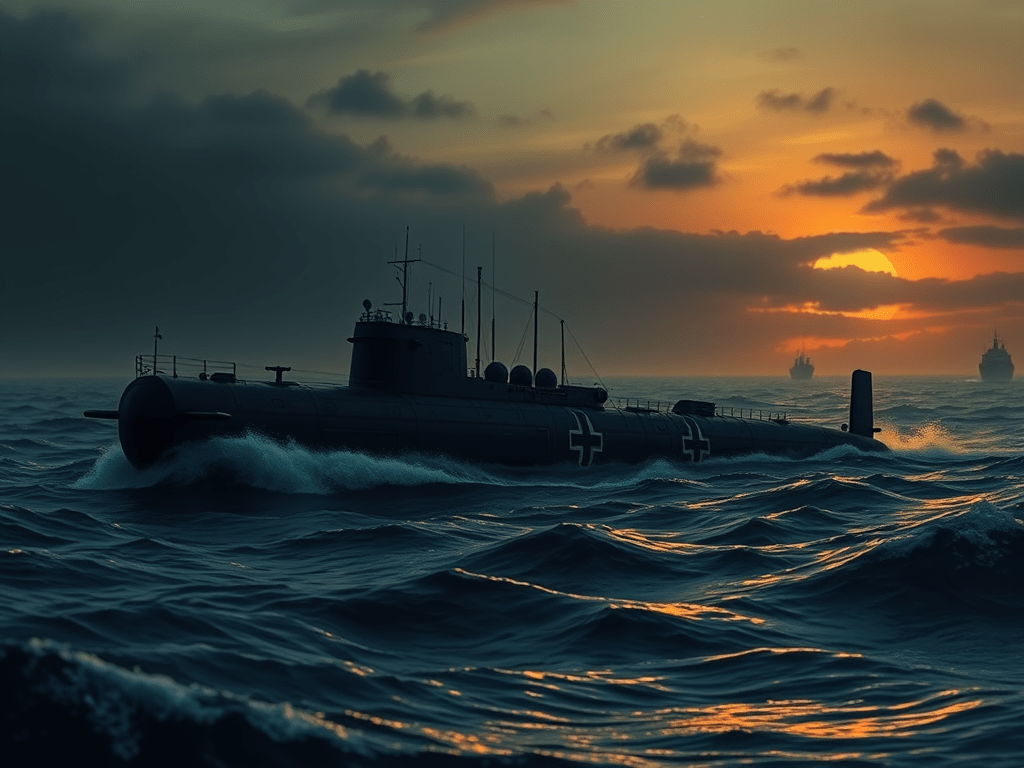

The English Channel is no calm pond. It’s a rough, deep, unpredictable stretch of water with tides, storms, and enemy submarines.

Building a fuel pipeline beneath it in 1944 seemed absurd — yet the Allies refused to give up.

Two main designs were created:

- The HAIS Cable

- Developed by British engineer H.A. Hammick and Siemens Brothers.

- It looked like a giant undersea electrical cable.

- Layers of lead, steel, and asphalt protected the inner rubber hose.

- Could pump up to 700 gallons per hour.

- The HAMEL Pipe

- A steel pipeline coiled around huge floating drums called Conundrums (because of their strange shape).

- These drums were towed by ships across the Channel, unspooling the pipe as they moved.

- Each section stretched over 30 miles long.

The pipelines were designed to connect Britain’s fuel depots — mainly on the Isle of Wight — to the beaches of Normandy after D-Day.

Operation Fortitude: Secrecy at All Costs

Everything about PLUTO was top secret.

It was so secret, in fact, that many of the workers laying the pipes didn’t know what they were for.

The operation was protected under the larger deception effort known as Operation Fortitude, which created fake armies and invasion plans to confuse the Germans.

Code names were given to every part of the project:

- BAMBI – the route from the Isle of Wight to Cherbourg.

- DUMBO – the route from Dungeness to Boulogne.

Even the word pipeline was never used in official communication. Engineers spoke of “cables,” “lines,” or “special conduits.”

Churchill personally followed the project’s progress and called it “one of the most daring engineering adventures of the war.”

Launch Day: The Pipeline Goes to War

The first PLUTO line — BAMBI — was laid in August 1944.

It stretched over 50 miles under the English Channel, from the Isle of Wight to Cherbourg in France.

Ships slowly towed the massive Conundrums, releasing the pipeline as they went.

Each drum weighed more than 250 tons and carried over 30 miles of coiled steel pipe.

The first attempt failed — the pipe snapped under pressure from the waves.

But the engineers adapted, strengthened the design, and tried again.

By September 1944, fuel was successfully flowing under the sea — from Britain straight to the heart of Europe.

By the end of the operation, 21 pipelines were laid across the Channel.

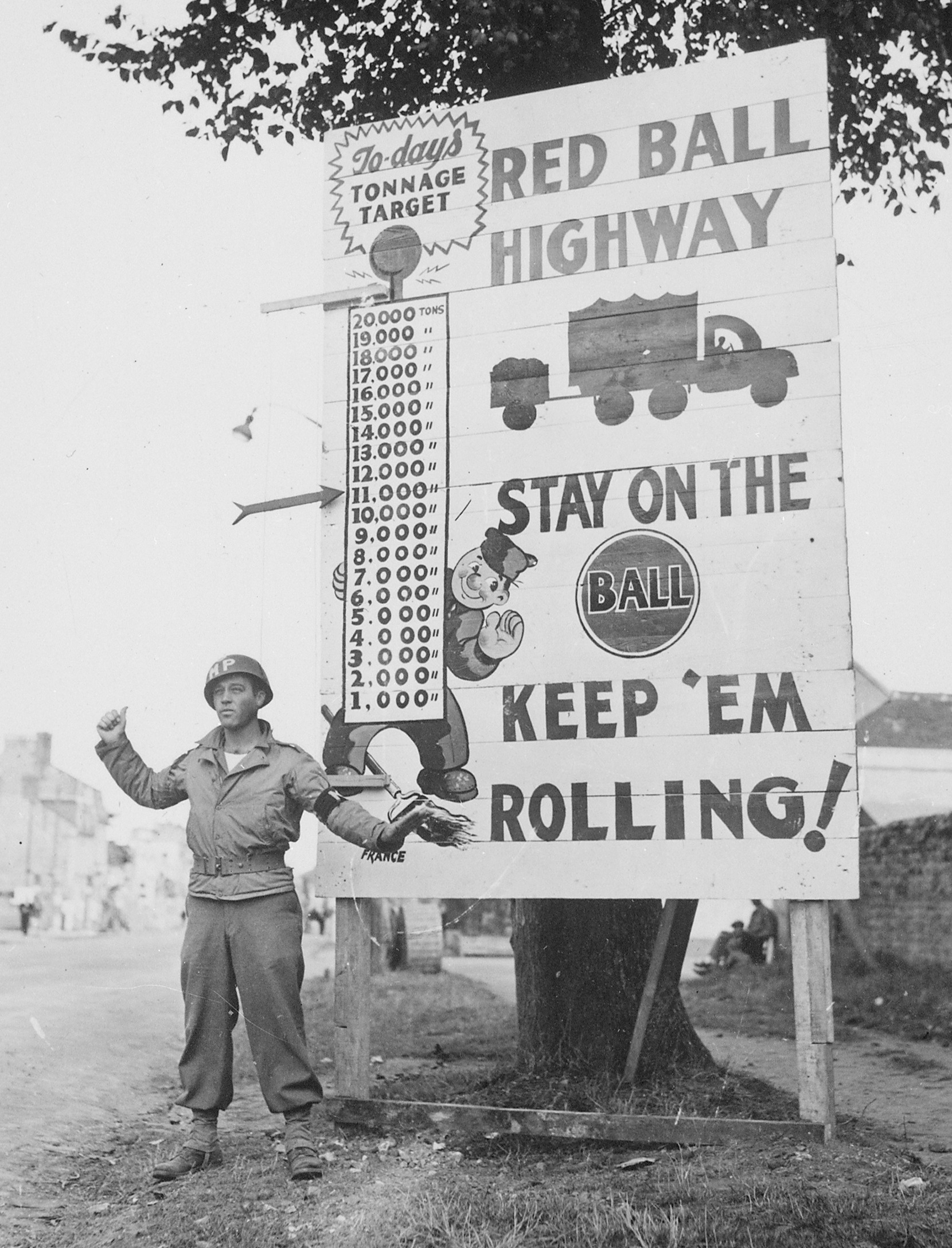

Feeding the Front: The Lifeblood of Victory

The PLUTO network supplied the advancing Allied armies with over 180 million gallons of fuel by the end of the war.

That’s enough to:

- Power 1 million tanks,

- Fly thousands of fighter missions,

- Or fuel every vehicle used in the liberation of France.

At its peak, the system delivered one million gallons per day, quietly and safely beneath the waves.

Unlike oil tankers — which could be sunk by German U-boats — PLUTO was invisible, invulnerable, and unstoppable.

The success of PLUTO meant the Allies could maintain their momentum all the way from Normandy to Berlin — without ever running dry.

Innovation Under Fire

The PLUTO project pushed the limits of wartime engineering.

- Underwater welding and pressure testing techniques pioneered for PLUTO laid the foundation for modern offshore pipelines.

- The Conundrum spools became the model for future deep-sea cable laying systems.

- The entire operation showed that logistics could win wars just as much as combat.

As historian Basil Liddell Hart once said:

“Victory in war is not gained by the brilliance of strategy, but by the strength of supply.”

PLUTO proved that statement beyond doubt.

Human Stories: The Engineers Who Made It Happen

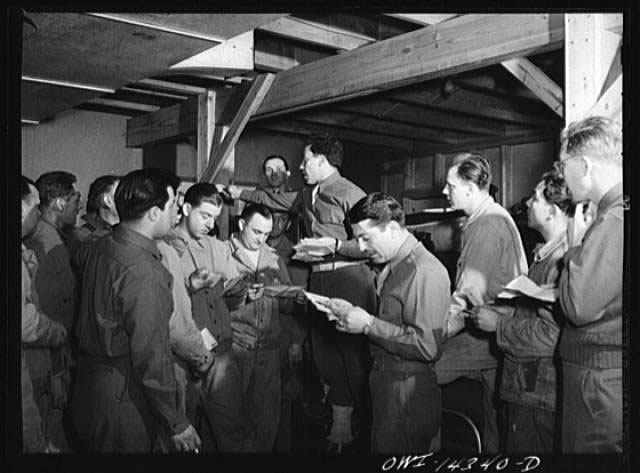

Thousands of workers, scientists, and soldiers contributed to PLUTO — often without knowing the full scale of what they were building.

- Geoffrey Lloyd, the British Petroleum Minister, coordinated resources across secret government departments.

- Lord Louis Mountbatten supported the project as part of Combined Operations.

- Civilians from oil companies, telecom firms, and steel factories all played roles in fabricating the components.

At one point, British street lamps were dismantled to recover the copper needed for pipeline wiring.

The project blurred the line between civilian industry and military necessity — a hallmark of total war.

Challenges and Failures Along the Way

PLUTO was not without its problems.

- Some of the early lines broke due to ocean pressure and seabed movement.

- The BAMBI line delivered less fuel than expected due to technical issues.

- The DUMBO line required constant maintenance as Allied forces advanced inland.

Yet the psychological and strategic value of PLUTO was enormous.

It gave Allied commanders confidence that their supply lines could stretch across the Channel — a vital factor in maintaining the offensive.

By early 1945, PLUTO had proven itself indispensable.

Aftermath and Legacy

When the war ended, the pipelines were no longer needed — but their legacy was just beginning.

The PLUTO project inspired:

- Modern underwater oil and gas pipelines.

- Transatlantic communication cables.

- Offshore energy infrastructure.

In peacetime, the same technology that fueled tanks would later fuel economies.

Today, remnants of PLUTO can still be seen along the coastlines of Britain and France.

Museums at Sandown and Arromanches preserve sections of the original pipes, and visitors can still trace the routes once known only to wartime engineers.